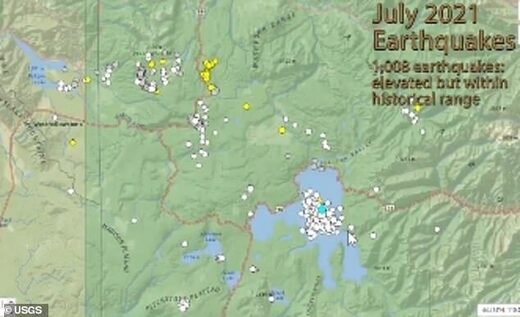

A swarm of more than 1,000 earthquakes ripped through Yellowstone National Park in July, which officials are calling a 'doozy' of a month.

This was the most seismic activity in the region since the Maple Creek swarm of more than 1,100 quakes shook the park in June 2017.

Although some may fear this increase in activity may mean 'the big one [earthquake] is near,' the US Geological Survey (USGS) says the earthquakes were not caused by magma, but rather groundwater moving through pre-existing faults.

The University of Utah Seismograph Stations, responsible for the operation and analysis of the Yellowstone Seismic Network, located 1,008 earthquakes in the park, with a whopping 764 beneath Yellowstone Lake.

The largest event was a 'quake with a 3.6 magnitude, located 11 miles below the lake's surface.

'While above average, this level of seismicity is not unprecedented, and it does not reflect magmatic activity,' the USGS wrote in its report.

'If magmatic activity were the cause of the quakes, we would expect to see other indicators, like changes in deformation style or thermal/gas emissions, but no such variations were detected.'

Yellowstone National Park sits in the northwest region of Wyoming and is home to bursting geysers, steam vents and bubbling pools.

At 3,472 square miles, the park is larger than the states of Rhode Island and Delaware combined.

Most of the land is in Wyoming, but some of the park spills into Montana and Idaho.

Earthquakes that strike the park usually happen in swarms and are a result of volcanic fluids flowing along 'small fractures in the shallow rocks over the magma, a pattern that has been noted in volcanoes around the world,' according to the park.

However, some of the swarms are associated with water that lubricates the faults, causing them to shake, or tectonic forces that trigger numerous earthquakes at once - which is what occurred in July.

July seismicity in Yellowstone was marked by seven earthquake swarms, which began on July 16.

Along with those in the Yellowstone Lake, the University of Utah also found the other earthquakes hit in groups of 12, 14, 20, 24 and 20.

Michael Poland, USGS geophysicist and Scientist-in-Charge at the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, told Accuweather: 'Yellowstone also has a tremendous amount of groundwater, and that's from all the snow that falls in that area. That's the highest area in the Rockies on average, and it's absolutely full of preexisting faults.'

As the underground pore space soaks up the snowmelt-turned-groundwater, it increases pressure on those nearby faults and can even cause them to fail.

'We typically see lots and lots of earthquakes when the snow melts or it gets into the ground and interacts with these faults,' Poland said.

'That's what caused earthquakes the last real big month for earthquakes back in June of 2017.'

Poland also explained magma fueled earthquakes leave behind different features and frequencies of shaking.

'Yellowstone is one of the most seismically active areas in the United States,' according to Yellowstone National Park's website.

'Approximately 700 to 3,000 earthquakes occur each year in the Yellowstone area; most are not felt.'

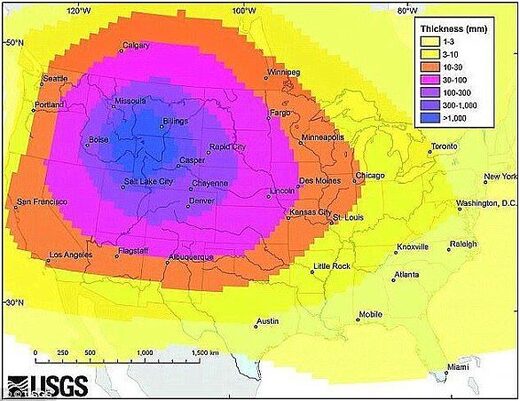

COULD AN ERUPTION AT THE YELLOWSTONE SUPERVOLCANO BE PREVENTED?

Recent research found a small magma chamber, known as the upper-crustal magma reservoir, beneath the surface

Nasa believes drilling up to six miles (10km) down into the supervolcano beneath Yellowstone National Park to pump in water at high pressure could cool it.

Despite the fact that the mission would cost $3.46 billion (£2.63 billion), Nasa considers it 'the most viable solution.'

Using the heat as a resource also poses an opportunity to pay for plan - it could be used to create a geothermal plant, which generates electric power at extremely competitive prices of around $0.10 (£0.08) per kWh.

But this method of subduing a supervolcano has the potential to backfire and trigger the supervolcanic eruption Nasa is trying to prevent.

'Drilling into the top of the magma chamber 'would be very risky;' however, carefully drilling from the lower sides could work.

Even besides the potential devastating risks, the plan to cool Yellowstone with drilling is not simple.

Doing so would be an excruciatingly slow process that one happen at the rate of one metre a year, meaning it would take tens of thousands of years to cool it completely.

And still, there wouldn't be a guarantee it would be successful for at least hundreds or possibly thousands of years.

WATCH: 'Thunderous Roar' Reverberates Across Yellowstone Park Sparking Fears Among Visitors

ALSO WATCH: Solar Cycle 25 is Rapidly Intensifying Into One of the Strongest on Record